Pythagoras's theorem in Babylonian mathematics

Pythagoras's theorem in Babylonian mathematics

In this article we examine four Babylonian tablets which all have some connection with Pythagoras's theorem. Certainly the Babylonians were familiar with Pythagoras's theorem. A translation of a Babylonian tablet which is preserved in the British museum goes as follows:-

The article Babylonian mathematics gives some background to how the civilisation came about and the mathematical background which they inherited.

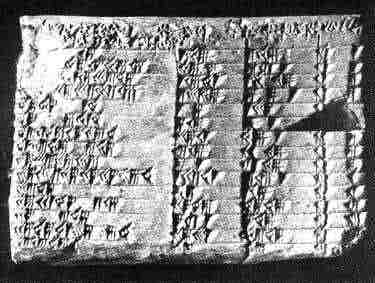

The four tablets which interest us here we will call the Yale tablet YBC 7289, Plimpton 322 (shown below), the Susa tablet, and the Tell Dhibayi tablet. Let us say a little about these tablets before describing the mathematics which they contain.

The Yale tablet YBC 7289 which we describe is one of a large collection of tablets held in the Yale Babylonian collection of Yale University. It consists of a tablet on which a diagram appears. The diagram is a square of side 30 with the diagonals drawn in. The tablet and its significance was first discussed in [5] and recently in [18].

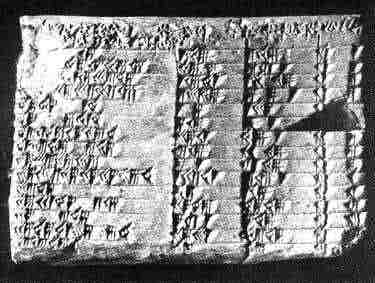

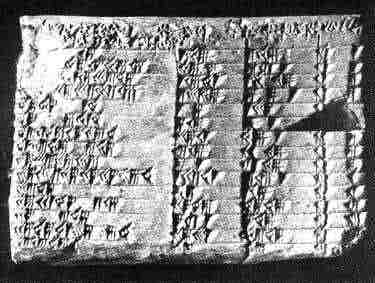

You can see from the picture that the top left hand corner of the tablet is damaged as and there is a large chip out of the tablet around the middle of the right hand side. Its date is not known accurately but it is put at between 1800 BC and 1650 BC. It is thought to be only part of a larger tablet, the remainder of which has been destroyed, and at first it was thought, as many such tablets are, to be a record of commercial transactions. However in [5] Neugebauer and Sachs gave a new interpretation and since then it has been the subject of a huge amount of interest.

The Susa tablet was discovered at the present town of Shush in the Khuzistan region of Iran. The town is about 350 km from the ancient city of Babylon. W K Loftus identified this as an important archaeological site as early as 1850 but excavations were not carried out until much later. The particular tablet which interests us here investigates how to calculate the radius of a circle through the vertices of an isosceles triangle.

Finally the Tell Dhibayi tablet was one of about 500 tablets found near Baghdad by archaeologists in 1962. Most relate to the administration of an ancient city which flourished in the time of Ibalpiel II of Eshunna and date from around 1750. The particular tablet which concerns us is not one relating to administration but one which presents a geometrical problem which asks for the dimensions of a rectangle whose area and diagonal are known.

Before looking at the mathematics contained in these four tablets we should say a little about their significance in understanding the scope of Babylonian mathematics. Firstly we should be careful not to read into early mathematics ideas which we can see clearly today yet which were never in the mind of the author. Conversely we must be careful not to underestimate the significance of the mathematics just because it has been produced by mathematicians who thought very differently from today's mathematicians. As a final comment on what these four tablets tell us of Babylonian mathematics we must be careful to realise that almost all of the mathematical achievements of the Babylonians, even if they were all recorded on clay tablets, will have been lost and even if these four may be seen as especially important among those surviving they may not represent the best of Babylonian mathematics.

There is no problem understanding what the Yale tablet YBC 7289 is about.

Here is a Diagram of Yale tablet

It has on it a diagram of a square with 30 on one side, the diagonals are drawn in and near the centre is written 1,24,51,10 and 42,25,35. Of course these numbers are written in Babylonian numerals to base 60. See our article on Babylonian numerals at THIS LINK. Now the Babylonian numbers are always ambiguous and no indication occurs as to where the integer part ends and the fractional part begins. Assuming that the first number is 1; 24,51,10 then converting this to a decimal gives 1.414212963 while √2 = 1.414213562. Calculating 30 × [ 1;24,51,10 ] gives 42;25,35 which is the second number. The diagonal of a square of side 30 is found by multiplying 30 by the approximation to √2.

This shows a nice understanding of Pythagoras's theorem. However, even more significant is the question how the Babylonians found this remarkably good approximation to √2. Several authors, for example see [2] and [4], conjecture that the Babylonians used a method equivalent to Heron's method. The suggestion is that they started with a guess, say . They then found which is the error. Then

This is certainly possible and the Babylonians' understanding of quadratics adds some weight to the claim. However there is no evidence of the algorithm being used in any other cases and its use here must remain no more than a fairly remote possibility. May I [EFR] suggest an alternative. The Babylonians produced tables of squares, in fact their whole understanding of multiplication was built round squares, so perhaps a more obvious approach for them would have been to make two guesses, one high and one low say and . Take their average and square it. If the square is greater than 2 then replace by this better bound, while if the square is less than 2 then replace a by . Continue with the algorithm.

Now this certainly takes many more steps to reach the sexagesimal approximation 1;24,51,10. In fact starting with and it takes 19 steps as the table below shows:

The tablet has four columns with 15 rows. The last column is the simplest to understand for it gives the row number and so contains 1, 2, 3, ... , 15. The remarkable fact which Neugebauer and Sachs pointed out in [5] is that in every row the square of the number in column 3 minus the square of the number in column 2 is a perfect square, say .

The first column is harder to understand, particularly since damage to the tablet means that part of it is missing. However, using the above notation, it is seen that the first column is just . Now so far so good, but if one were writing down Pythagorean triples one would find much easier ones than those which appear in the table. For example the Pythagorean triple 3, 4 , 5 does not appear neither does 5, 12, 13 and in fact the smallest Pythagorean triple which does appear is 45, 60, 75 (15 times 3, 4 , 5). Also the rows do not appear in any logical order except that the numbers in column 1 decrease regularly. The puzzle then is how the numbers were found and why are these particular Pythagorean triples are given in the table.

Several historians (see for example [2]) have suggested that column 1 is connected with the secant function. However, as Joseph comments [4]:-

To give a fair discussion of Plimpton 322 we should add that not all historians agree that this tablet concerns Pythagorean triples. For example Exarchakos, in [17], claims that the tablet is connected with the solution of quadratic equations and has nothing to do with Pythagorean triples:-

Here is a Diagram of Susa tablet

Here we have labelled the triangle and the centre of the circle is . The perpendicular is drawn from to meet the side . Now the triangle is a right angled triangle so, using Pythagoras's theorem , so . Let the radius of the circle by . Then and . Using Pythagoras's theorem again on the triangle we have

and so or, in sexagesimal, 31;15.

Finally consider the problem from the Tell Dhibayi tablet. It asks for the sides of a rectangle whose area is 0;45 and whose diagonal is 1;15. Now this to us is quite an easy exercise in solving equations. If the sides are we have and . We would substitute into the second equation to obtain a quadratic in which is easily solved. This however is not the method of solution given by the Babylonians and really that is not surprising since it rests heavily on our algebraic understanding of equations. The way the Tell Dhibayi tablet solves the problem is, I would suggest, actually much more interesting than the modern method.

Here is the method from the Tell Dhibayi tablet. We preserve the modern notation and as each step for clarity but we do the calculations in sexagesimal notation (as of course does the tablet).

In this article we examine four Babylonian tablets which all have some connection with Pythagoras's theorem. Certainly the Babylonians were familiar with Pythagoras's theorem. A translation of a Babylonian tablet which is preserved in the British museum goes as follows:-

4 is the length and 5 the diagonal. What is the breadth ?All the tablets we wish to consider in detail come from roughly the same period, namely that of the Old Babylonian Empire which flourished in Mesopotamia between 1900 BC and 1600 BC.

Its size is not known.

4 times 4 is 16.

5 times 5 is 25.

You take 16 from 25 and there remains 9.

What times what shall I take in order to get 9 ?

3 times 3 is 9.

3 is the breadth.

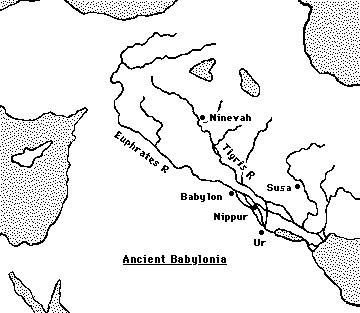

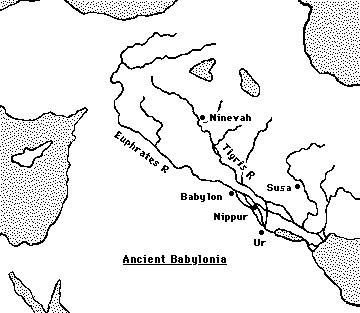

Here is a map of the region where the Babylonian civilisation flourished.

The article Babylonian mathematics gives some background to how the civilisation came about and the mathematical background which they inherited.

The four tablets which interest us here we will call the Yale tablet YBC 7289, Plimpton 322 (shown below), the Susa tablet, and the Tell Dhibayi tablet. Let us say a little about these tablets before describing the mathematics which they contain.

The Yale tablet YBC 7289 which we describe is one of a large collection of tablets held in the Yale Babylonian collection of Yale University. It consists of a tablet on which a diagram appears. The diagram is a square of side 30 with the diagonals drawn in. The tablet and its significance was first discussed in [5] and recently in [18].

Plimpton 322 is the tablet numbered 322 in the collection of G A Plimpton housed in Columbia University.

You can see from the picture that the top left hand corner of the tablet is damaged as and there is a large chip out of the tablet around the middle of the right hand side. Its date is not known accurately but it is put at between 1800 BC and 1650 BC. It is thought to be only part of a larger tablet, the remainder of which has been destroyed, and at first it was thought, as many such tablets are, to be a record of commercial transactions. However in [5] Neugebauer and Sachs gave a new interpretation and since then it has been the subject of a huge amount of interest.

The Susa tablet was discovered at the present town of Shush in the Khuzistan region of Iran. The town is about 350 km from the ancient city of Babylon. W K Loftus identified this as an important archaeological site as early as 1850 but excavations were not carried out until much later. The particular tablet which interests us here investigates how to calculate the radius of a circle through the vertices of an isosceles triangle.

Finally the Tell Dhibayi tablet was one of about 500 tablets found near Baghdad by archaeologists in 1962. Most relate to the administration of an ancient city which flourished in the time of Ibalpiel II of Eshunna and date from around 1750. The particular tablet which concerns us is not one relating to administration but one which presents a geometrical problem which asks for the dimensions of a rectangle whose area and diagonal are known.

Before looking at the mathematics contained in these four tablets we should say a little about their significance in understanding the scope of Babylonian mathematics. Firstly we should be careful not to read into early mathematics ideas which we can see clearly today yet which were never in the mind of the author. Conversely we must be careful not to underestimate the significance of the mathematics just because it has been produced by mathematicians who thought very differently from today's mathematicians. As a final comment on what these four tablets tell us of Babylonian mathematics we must be careful to realise that almost all of the mathematical achievements of the Babylonians, even if they were all recorded on clay tablets, will have been lost and even if these four may be seen as especially important among those surviving they may not represent the best of Babylonian mathematics.

There is no problem understanding what the Yale tablet YBC 7289 is about.

Here is a Diagram of Yale tablet

It has on it a diagram of a square with 30 on one side, the diagonals are drawn in and near the centre is written 1,24,51,10 and 42,25,35. Of course these numbers are written in Babylonian numerals to base 60. See our article on Babylonian numerals at THIS LINK. Now the Babylonian numbers are always ambiguous and no indication occurs as to where the integer part ends and the fractional part begins. Assuming that the first number is 1; 24,51,10 then converting this to a decimal gives 1.414212963 while √2 = 1.414213562. Calculating 30 × [ 1;24,51,10 ] gives 42;25,35 which is the second number. The diagonal of a square of side 30 is found by multiplying 30 by the approximation to √2.

This shows a nice understanding of Pythagoras's theorem. However, even more significant is the question how the Babylonians found this remarkably good approximation to √2. Several authors, for example see [2] and [4], conjecture that the Babylonians used a method equivalent to Heron's method. The suggestion is that they started with a guess, say . They then found which is the error. Then

and they had a better approximation since if is small then will be very small. Continuing the process with this better approximation to √2 yieds a still better approximation and so on. In fact as Joseph points out in [4], one needs only two steps of the algorithm if one starts with to obtain the approximation 1;24,51,10.

This is certainly possible and the Babylonians' understanding of quadratics adds some weight to the claim. However there is no evidence of the algorithm being used in any other cases and its use here must remain no more than a fairly remote possibility. May I [EFR] suggest an alternative. The Babylonians produced tables of squares, in fact their whole understanding of multiplication was built round squares, so perhaps a more obvious approach for them would have been to make two guesses, one high and one low say and . Take their average and square it. If the square is greater than 2 then replace by this better bound, while if the square is less than 2 then replace a by . Continue with the algorithm.

Now this certainly takes many more steps to reach the sexagesimal approximation 1;24,51,10. In fact starting with and it takes 19 steps as the table below shows:

step decimal sexagesimal 1 1.500000000 1;29,59,59 2 1.250000000 1;14,59,59 3 1.375000000 1;22,29,59 4 1.437500000 1;26,14,59 5 1.406250000 1;24,22,29 6 1.421875000 1;25,18,44 7 1.414062500 1;24,50,37 8 1.417968750 1;25, 4,41 9 1.416015625 1;24,57,39 10 1.415039063 1;24,54, 8 11 1.414550781 1;24,52,22 12 1.414306641 1;24,51;30 13 1.414184570 1;24,51; 3 14 1.414245605 1;24,51;17 15 1.414215088 1;24,51;10 16 1.414199829 1;24,51; 7 17 1.414207458 1;24,51; 8 18 1.414211273 1;24,51; 9 19 1.414213181 1;24,51;10However, the Babylonians were not frightened of computing and they may have been prepared to continue this straightforward calculation until the answer was correct to the third sexagesimal place.

Next we look again at Plimpton 322

The tablet has four columns with 15 rows. The last column is the simplest to understand for it gives the row number and so contains 1, 2, 3, ... , 15. The remarkable fact which Neugebauer and Sachs pointed out in [5] is that in every row the square of the number in column 3 minus the square of the number in column 2 is a perfect square, say .

So the table is a list of Pythagorean integer triples. Now this is not quite true since Neugebauer and Sachs believe that the scribe made four transcription errors, two in each column and this interpretation is required to make the rule work. The errors are readily seen to be genuine errors, however, for example 8,1 has been copied by the scribe as 9,1.

The first column is harder to understand, particularly since damage to the tablet means that part of it is missing. However, using the above notation, it is seen that the first column is just . Now so far so good, but if one were writing down Pythagorean triples one would find much easier ones than those which appear in the table. For example the Pythagorean triple 3, 4 , 5 does not appear neither does 5, 12, 13 and in fact the smallest Pythagorean triple which does appear is 45, 60, 75 (15 times 3, 4 , 5). Also the rows do not appear in any logical order except that the numbers in column 1 decrease regularly. The puzzle then is how the numbers were found and why are these particular Pythagorean triples are given in the table.

Several historians (see for example [2]) have suggested that column 1 is connected with the secant function. However, as Joseph comments [4]:-

This interpretation is a trifle fanciful.Zeeman has made a fascinating observation. He has pointed out that if the Babylonians used the formulas to generate Pythagorean triples then there are exactly 16 triples satisfying , and having a finite sexagesimal expansion (which is equivalent to having 2, 3, and 5 as their only prime divisors). Now 15 of the 16 Pythagorean triples satisfying Zeeman's conditions appear in Plimpton 322. Is it the earliest known mathematical classification theorem? Although I cannot believe that Zeeman has it quite right, I do feel that his explanation must be on the right track.

To give a fair discussion of Plimpton 322 we should add that not all historians agree that this tablet concerns Pythagorean triples. For example Exarchakos, in [17], claims that the tablet is connected with the solution of quadratic equations and has nothing to do with Pythagorean triples:-

... we prove that in this tablet there is no evidence whatsoever that the Babylonians knew the Pythagorean theorem and the Pythagorean triads.I feel that the arguments are weak, particularly since there are numerous tablets which show that the Babylonians of this period had a good understanding of Pythagoras's theorem. Other authors, although accepting that Plimpton 322 is a collection of Pythagorean triples, have argued that they had, as Viola writes in [31], a practical use in giving a:-

... general method for the approximate computation of areas of triangles.The Susa tablet sets out a problem about an isosceles triangle with sides 50, 50 and 60. The problem is to find the radius of the circle through the three vertices.

Here is a Diagram of Susa tablet

Here we have labelled the triangle and the centre of the circle is . The perpendicular is drawn from to meet the side . Now the triangle is a right angled triangle so, using Pythagoras's theorem , so . Let the radius of the circle by . Then and . Using Pythagoras's theorem again on the triangle we have

.

So

giving

and so or, in sexagesimal, 31;15.

Finally consider the problem from the Tell Dhibayi tablet. It asks for the sides of a rectangle whose area is 0;45 and whose diagonal is 1;15. Now this to us is quite an easy exercise in solving equations. If the sides are we have and . We would substitute into the second equation to obtain a quadratic in which is easily solved. This however is not the method of solution given by the Babylonians and really that is not surprising since it rests heavily on our algebraic understanding of equations. The way the Tell Dhibayi tablet solves the problem is, I would suggest, actually much more interesting than the modern method.

Here is the method from the Tell Dhibayi tablet. We preserve the modern notation and as each step for clarity but we do the calculations in sexagesimal notation (as of course does the tablet).

Compute = 1;30.

Subtract from 1;33,45 to get 0;3,45.

Take the square root to obtain 0;15.

Divide by 2 to get 0;7,30.

Divide 0;3,45 by 4 to get 0;0,56,15.

Add 0;45 to get 0;45,56,15.

Take the square root to obtain 0;52,30.

Add 0;52,30 to 0;7,30 to get .

Subtract 0;7,30 from 0;52,30 to get 0;45.

Hence the rectangle has sides and 0;45.

Is this not a beautiful piece of mathematics! Remember that it is 3750 years old. We should be grateful to the Babylonians for recording this little masterpiece on tablets of clay for us to appreciate today.

Subtract from 1;33,45 to get 0;3,45.

Take the square root to obtain 0;15.

Divide by 2 to get 0;7,30.

Divide 0;3,45 by 4 to get 0;0,56,15.

Add 0;45 to get 0;45,56,15.

Take the square root to obtain 0;52,30.

Add 0;52,30 to 0;7,30 to get .

Subtract 0;7,30 from 0;52,30 to get 0;45.

Hence the rectangle has sides and 0;45.

References (show)

- A Aaboe, Episodes from the Early History of Mathematics (1964).

- R Calinger, A conceptual history of mathematics (Upper Straddle River, N. J., 1999).

- G Ifrah, A universal history of numbers : From prehistory to the invention of the computer (London, 1998).

- G G Joseph, The crest of the peacock (London, 1991).

- O Neugebauer and A Sachs, Mathematical Cuneiform Texts (New Haven, CT., 1945).

- B L van der Waerden, Science Awakening (Groningen, 1954).

- B L van der Waerden, Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations (New York, 1983).

- A Ahmad, On Babylonian and Vedic square root of 2, Ganita Bharati 16 (1-4) 1994), 1-4.

- C Anagnostakis and B R Goldstein, On an error in the Babylonian table of Pythagorean triples, Centaurus 18 (1973/74), 64-66.

- J K Bidwell, A Babylonian geometrical algebra, College Math. J. 17 (1) (1986), 22-31.

- E M Bruins, Fermat problems in Babylonian mathematics, Janus 53 (1966), 194-211.

- E M Bruins, On Plimpton 322. Pythagorean numbers in Babylonian mathematics, Nederl. Akad. Wetensch., Proc. 52 (1949), 629-632.

- E M Bruins, Pythagorean triads in Babylonian mathematics, Math. Gaz. 41 (1957), 25-28.

- E M Bruins, Pythagorean triads in Babylonian mathematics. The errors on Plimpton 322, Sumer 11 (1955), 117-121.

- E M Bruins, Square roots in Babylonian and Greek mathematics, Nederl. Akad. Wetensch. Proc. 51 (1948), 332-341.

- M Caveing, La tablette babylonienne AO 17264 du Musée du Louvre et le problème des six frères, Historia Math. 12 (1) (1985), 6-24.

- T G Exarchakos, Babylonian mathematics and Pythagorean triads, Bull. Greek Math. Soc. 37 (1995), 29-47.

- D Fowler and E Robson, Square root approximations in old Babylonian mathematics: YBC 7289 in context, Historia Math. 25 (4) (1998), 366-378.

- J Friberg, Methods and traditions of Babylonian mathematics. II. An old Babylonian catalogue text with equations for squares and circles, J. Cuneiform Stud. 33 (1) (1981), 57-64.

- J Friberg, Methods and traditions of Babylonian mathematics: Plimpton 322, Pythagorean triples and the Babylonian triangle parameter equations, Historia Math. 8 (3) (1981), 277-318.

- R J Gillings, Unexplained error in Babylonian cuneiform tablet, Plimpton 322, Australian J. Sci. 16 (1953), 54-56.

- R J Gillings, and C L Hamblin, Babylonian sexagesimal reciprocal tables, Austral. J. Sci. 27 (1964), 139-141.

- J Hoyrup, The Babylonian cellar text BM 85200+ VAT 6599: Retranslation and analysis, in Amphora (Basel, 1992), 315-358.

- S Ilic, M S Petkovic and D Herceg, A note on Babylonian square-root algorithm and related variants, Novi Sad J. Math. 26 (1) (1996), 155-162.

- M Linton, Babylonian triples, Bull. Inst. Math. Appl. 24 (3-4) (1988), 37-41.

- K Muroi, Extraction of cube roots in Babylonian mathematics, Centaurus 31 (3-4) (1988), 181-188.

- K Muroi, Extraction of square roots in Babylonian mathematics, Historia Sci. (2) 9 (2) (1999), 127-133.

- K Muroi, The expressions of zero and of squaring in the Babylonian mathematical text VAT 7537, Historia Sci. (2) 1 (1) (1991), 59-62.

- D J de Solla Price, The Babylonian "Pythagorean triangle" tablet, Centaurus 10 (1964/1965), 1-13.

- O Schmidt, On Plimpton 322: Pythagorean numbers in Babylonian mathematics, Centaurus 24 (1980), 4-13.

- T Viola, On the list of Pythagorean triples ("Plimpton 322") and on a possible use of it in old Babylonian mathematics (Italian), Boll. Storia Sci. Mat. 1 (2) (1981), 103-132.

Written by J J O'Connor and E F Robertson

Last Update December 2000

Last Update December 2000