Around the Galileo sites of Florence

I [EFR] spent 10 days in Florence at the end of July 2025 with my wife Helena and our son David. We visited most, but not all, of the places in the journey we give below but information about those we did not visit was given in the Galileo Museum. The route from 3 to 8 is an easy walk. The walk from 1 to 3 is about 1.4 km, 8-9 is 800 m, 9-10 about 750 m, 10-11 is 2 km, 11-12 is just under 1 km, 12-13 is 2.3 km but 13 is close to 14. The route, of course, does zig zag and you could go from 7 to 11 directly on a walk of 900 m. The walk is imaginary; we visited the sites of different days.

Click on a link below to go to that place

Click on a link below to go to that place

- Palazzo dei Cartelloni

- Liceo Ginnasio Galileo Galilei

- Casa Buonarroti

- Church of Santa Croce

- Biblioteca Nationale Centrale di Firenze

- Galileo Museum

- Uffizi Gallery

- Church of Santa Trinita

- Church of Santa Maria del Carmine

- Villa dell'Ombrellino

- Tribune of Galileo

- Galileo's house

- Villa Il Gioiello

- Convent of San Matteo

The site numbers are in red. Sites 13 and 14 are about 1km off the South of the map.

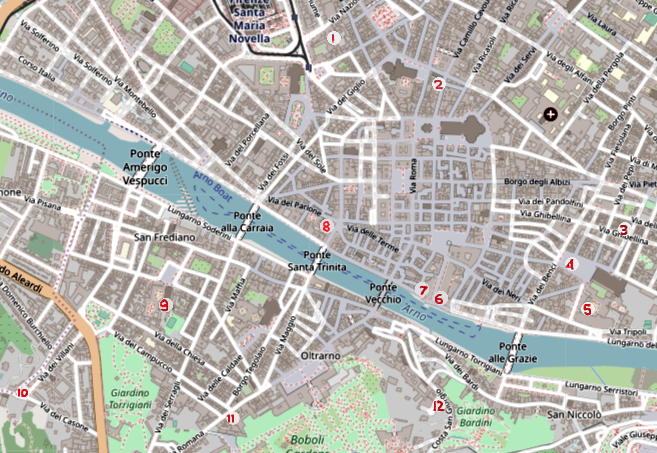

1. Palazzo dei Cartelloni.

Via Sant'Antonino.

Also known as Palazzo Viviani, this was Viviani's residence and there are marble cartouches on the facade displaying texts on Galileo's life and work.

Vincenzo Viviani was Galileo's last pupil and lived in Galileo's home from 1639 to 1642 when Galileo was under house arrest. Following Galileo's death in 1642, Viviani wanted to create a memorial to honour Galileo's achievements but this proved difficult since the Church did not want someone they had condemned for "vehement suspicion of heresy" to have a monument. In 1690 Viviani decided to defy the papal ban and make his home, the Palazzo dei Cartelloni, into the monument. Before Viviani bought the Palazzo dei Cartelloni it had been owned by Francesco del Giocondo, whose wife Monna Lisa Gherardini, known as "Gioconda", is claimed to be the woman painted by Leonardo da Vinci. Viviani created a monument to Galileo on the facade of the Palazzo dei Cartelloni. He completed the work in 1693 and you can see the result in the two pictures below:

The two panels give details of Galileo's discoveries. The right hand panel describes his discovery of the four moons of Jupiter while the left hand cartouche describes his discovery of parabolic motion of projectiles. The bust of Galileo in the centre was made by Giovanni Battista Foggini who copied the bust of Galileo made by Giovanni Caccini in 1610.

Following Viviani's death in 1703, the Palazzo dei Cartelloni was inherited by his nephew, Abbot Paolo Panzanini, then passed to Giovanni Battista Nelli's son who published details of the cartouches on the facade of the Palazzo dei Cartelloni in his book "Galileo's Life and Literary Commerce". Eventually, in 1999, the Studio Arts College International took possession of the Palazzo and used it as an exhibition space, classrooms, a library, offices, and an art conservation laboratory. They taught undergraduate and graduate level students there but closed their teaching in 2021 blaming COVID-19 for their financial difficulties.

From the Via Sant'Antonino take the Via del Conti, then the Via Ferdinando Zannetti to the Piazza del Duomo. Take the Via Martelli to the Liceo Ginnasio Galileo Galilei.

2. Liceo Ginnasio Galileo Galilei.

Via Martelli.

Originally part of a 16th century school, the school was named for Galileo in 1878.

In 1554 Cosimo I de' Medici granted the Society of Jesus the right to built a Jesuit College near the church of San Giovannino degli Scolopi located on the corner of Via Martelli and Via Gori. Although space was limited, construction of both a church and college began. For various reasons work progressed very slowly and by the middle of the 17th century only the part of the college on Via Martelli was complete. In 1775 the Piarists purchased the building and moved their school there. The Piarists continued to own the building after they moved their school to other premises but in 1878 they ceded part of the building to house a Royal Gymnasium, which took the name "Galileo." A Lyceum was also added to the building in 1884.

Here is a picture taken while I was enjoying a coffee and snack in a cafe opposite the Liceo Ginnasio Galileo Galilei.

Returning along the Via Martelli to the Piazza del Duomo, walk round the Duomo, then down the Via del Proconsolo to the Via Ghibellina.

3. Casa Buonarroti.

Via Ghibellina.

Museum with a portrait of Galileo.

The Casa Buonarroti was purchased by Michelangelo in 1508 and later remodelled by the Buonarroti family. The Institute and Museum of the History of Science tells us about the wonderful fresco with Galileo.

The splendid building as we see it today was designed in the first half of the 17th century by Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger. The house was decorated by famous artists to glorify the family and its illustrious ancestor. In the "Studio", the rich iconography also shows clear references to science. Domenico Pugliani portrayed the physicists and the simplists, Cecco Bravo (Francesco Montelatici) portrayed the mathematicians and astronomers. In the latter fresco can be seen, along with scientific instruments such as an armillary sphere and a quadrant, the figure of Galileo Galilei, who with his telescope and an open book before him is showing the surface of the Moon, probably an allusion to the Sidereus nuncius [Starry Messenger] (Venice, 1610). The work was completed in the years 1633-1637, that is, while Galileo was still alive and had already been condemned by the Court of the Inquisition. The patron thus showed remarkable courage in celebrating a man who was at the time "strongly suspected of heresy".

From the Via Ghibellina take the Via delle Pinzochere to Santa Croce.

4. Church of Santa Croce.

Piazza Santa Croce.

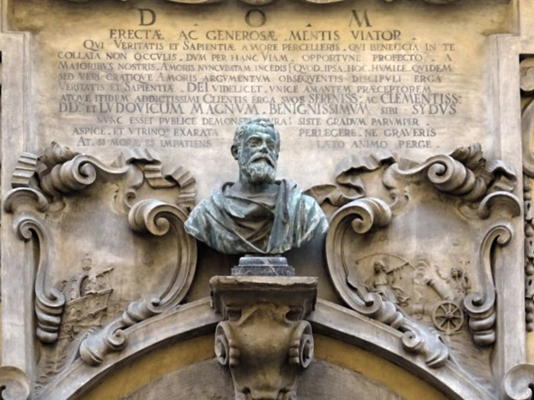

Contains the monumental tomb of Galileo.

Construction of the Church of Santa Croce began in 1294 led by Arnolfo di Cambio. It progressed slowly but wonderful frescos were painted by leading artists which mean that the church is today a wonderful art gallery. The church was consecrated in 1442 and became the burial place for the leading artists and scientists of Florence. When Galileo died in 1642, because he had been condemned by the Inquisition, he was buried, almost secretly, in a small room near the Novitiate chapel in Santa Croce. A plaque commemorating Galileo's first burial place, 1674 and 1737, is now seen in the Medici Chapel of Santa Croce.

The Grand Duke Gian Gastone de' Medici (1671-1737) aimed to modernise the State of Tuscany and limit the power of the Church. Almost 100 years after Galileo's death, he organised the construction of a monumental tomb to him in Santa Croce. It was designed by Giulio Foggini and the work was carried out by Foggini's two sons Giovanni Battista and Vincenzo along with Foggini's pupil Girolamo Ticciati. It was completed and Galileo's body moved to that site in 1737. When his remains was disinterred from its original burial place the remains of a young woman were discovered beside it. It is believed this was Sister Maria Celeste, Galileo's daughter, who died 8 years before her father in 1634 at the age of 33. Her remains and also those of Viviani were reburied under Galileo's monumental tomb.

The Catalogue of the works of Santa Croce gives the following information:

The sarcophagus, with two statues on either side, sits on a tall, three-part plinth. On the left Astronomy holds a parchment with sunspots carved by Vincenzo Foggini, while on the right Geometry displays a plank on an incline demonstrating the equation of falling bodies by Girolamo Ticciati. Above the tomb, a niche modelled to resemble a shell contains a bust of Galileo by Giovan Battista Foggini, who also designed the monument as a whole, and is topped by the family crest. Galileo is shown gazing at the heavens while clutching a telescope in his right hand, while his left hand rests on a celestial globe set on a pile of books and a compass. In the centre of the scroll we see the planet Jupiter with its moons, which Galileo discovered and christened the "Medici planets". Below, a lengthy inscription composed by Simone di Bindo Peruzzi celebrates the great man.

Of course there are many famous people with tombs or memorials in Santa Croce. Of those with a biography in MacTutor I saw Leone Battista Alberti's tomb, and memorials to Enrico Fermi and Florence Nightingale. Here is Alberti's tomb and the memorials to Fermi and Nightingale.

From the Piazza Santa Croce take the Via Antonio Magliabechi to the Biblioteca Nationale Centrale di Firenze.

5. Biblioteca Nationale Centrale di Firenze.

Piazza dei Cavalleggeri.

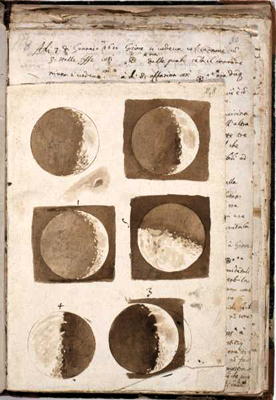

Contains more than 300 autograph manuscripts of Galileo.

The Library originated from the book collection of Antonio Magliabechi, consisting of approximately 30,000 volumes, bequeathed to the city of Florence in 1714. In 1737, the Grand Ducal administration established that works published in Florence be deposited there, and in 1743, the requirement was extended to those published throughout Tuscany. The Library opened to the public in 1747. In 1861, the Palatine Library, established by Grand Duke Ferdinand III of Lorraine, was incorporated into it.

The collection of Galileo's papers, consisting of 347 manuscripts, is one of the series of the Palatine Library. In 1818, Grand Duke Ferdinand III purchased Galileo's papers which had been collected by their ancestor, Giovan Battista Clemente, from the heirs of Viviani's friend Giovanni Battista Nelli. Clemente had dedicated his life to recovering every document belonging to Galileo, thus reuniting almost all of Galileo's writings that had been lost in various inheritances. The prince donated the collection to the Palatine Library in 1822, which in 1886 received another group of 40 files donated by Antonio Favaro (1847-1922).

Here is an example of one of the manuscripts.

Take the Lungarno Generale Diaz alongside the River Arno to the Piazza dei Giudici.

6. Galileo Museum.

Piazza dei Giudici.

Contains Room VII, Galileo's New World.

The Museo Galileo, the Galileo Museum, only took that name in 2010. Before that time it was known as the Museo di Storia della Scienza, the History of Science Museum. The Istituto di Storia della Scienza, History of Science Institute, was founded on 7 May 1925 with Andrea Corsini as its director. He wrote to the rector of the University of Florence, Giulio Chiarugi, on 29 October 1925 saying:-

We could easily establish the most beautiful Institute and Museum of the history of science in the world.The University of Florence owned several collections of historical instruments which became part of the museum. In the information we give below for the Uffizi Gallery there are details of how some of the instruments came from the collection of Cosimo I de' Medici and were displayed in the Uffizi Gallery until 1775. They were displayed in the Museum of Physics in the Palazzo Torrigiani and then the Tribune of Galileo from 1841. For the text of the history of Florence's scientific instruments displayed in the Galileo Museum, see THIS LINK.

Instruments owned by Galileo displayed in the Museum are his telescopes and his Geometric and Military Compasses. Here are pictures of them.

The picture of the telescopes shows the only two extant telescopes known with certainty to have been used by Galileo. The lower one is made of wood and leather and is 92.7 cm long. Covered with red leather with gold tooling, it was donated by Galileo to Cosimo II de' Medici after the Sidereus nuncius was published on 13 March 1610. Also in the same picture is the objective lens which Galileo used for many observations in 1609-10. He donated it to Grand Duke Ferdinando II. The lens is displayed in an ebony frame which the Medici commissioned Vittorio Crosten to create in 1677. Despite having the frame for protection, the lens was accidently cracked around the time it was transferred to the Tribune of Galileo in 1841.

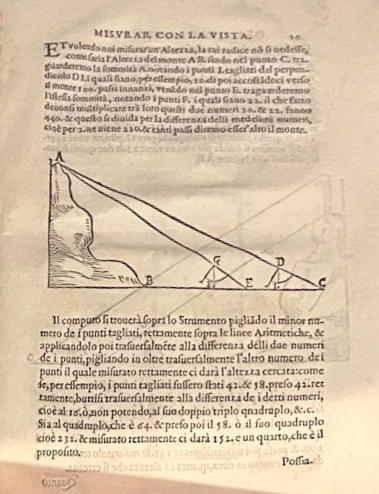

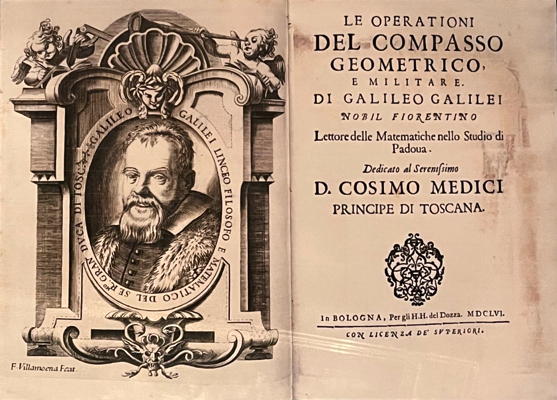

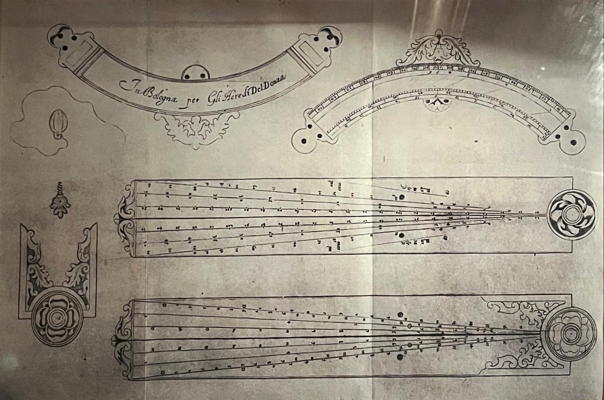

The Geometric and Military Compasses are made of brass and date from about 1606. They are 25.6 cm long and 36 cm wide when opened. There are seven scales engraved on the legs designed for solving problems with geometrical and arithmetical operations. It had other scales which allowed it to be used as a gunner's quadrant, an astronomical quadrant, a clinometer which is used to measure the angle of elevation, or a quadrant for measuring by sight. Galileo published the book Le operazioni del compasso geometrico et militare in Padua in 1606 which explained the operations of the compasses. It was his first published work.

Here is my photograph of the book displayed in the Galileo Museum.

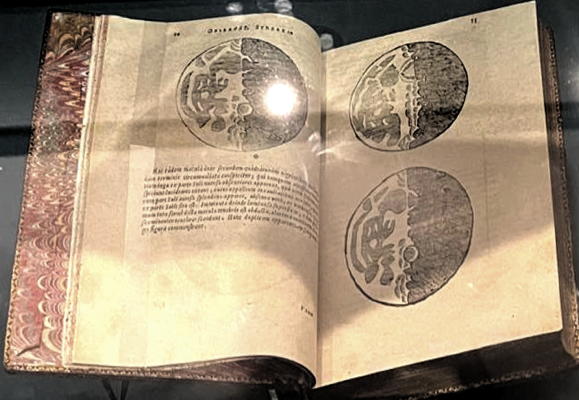

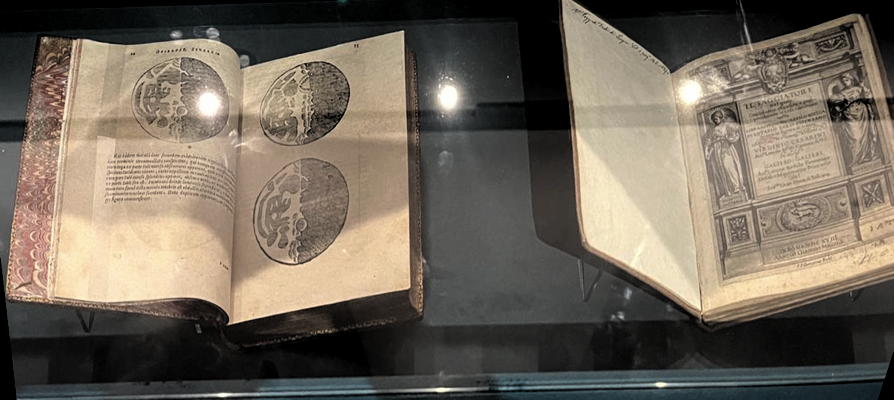

Also displayed in the Museum is the version published in Galileo's collected works of 1656. Here are two pictures I took of this book.

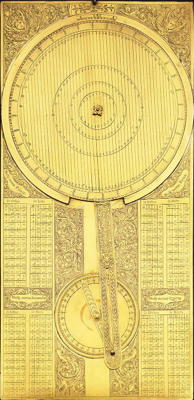

With his telescopes, Galileo observed the four satellites of Jupiter in January 1610. All four were equally bright and he found it difficult to distinguish them and find the length of their orbits round Jupiter. He developed a diagram called the Jovilabe to calculate the orbits. Since the positions of the satellites varied due to the relative positions of the earth and Jupiter, he calculated the positions of the satellites as would be seen from the sun which could then be corrected for observations from the earth using the Earth-Jupiter-Sun angle. In the second half of the 17th century an unknown maker made Galileo's Jovilabe diagram into an instrument which is displayed in the Galileo Museum.

This instrument has four numerical tables showing the mean motions of each of the four moons. There are two disks of different diameters with a rod between them which rotates the disks. They are used correct the view from the Sun to that observed from the Earth using the Earth-Jupiter-Sun angle. Galileo realised that Jupiter's satellites provided a clock which would allow an observer on the earth to determine their longitude. This would have major military and trading implications and Galileo offered his tables to the King of Spain in 1611, again in 1612, again in 1616 and finally in 1627. The Spanish realised the difficulty of observing the satellites from a moving ship and Galileo tried to convince them it was possible designing a helmet with a telescope attached by a hinge.

To determine longitude at sea, Galileo also proposed a pendulum clock as an accurate time keeper. Galileo's design of a pendulum clock was reproduced in drawings by Viviani and Galileo's son Vincenzo and sent to the Dutch scholar Laurens Reael in June 1637. Based on these drawing, Eustachio Porcellotti made a pendulum clock in 1877 which is displayed in the Galileo Museum.

The Museum contains several books by Galileo. Here is a picture I took of the first volume of the Opere (1656), the Sidereus nuncius (from this 1656 Opere) and the Il saggiatore (1623)

and one of the Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (1632) and the Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze (1638).

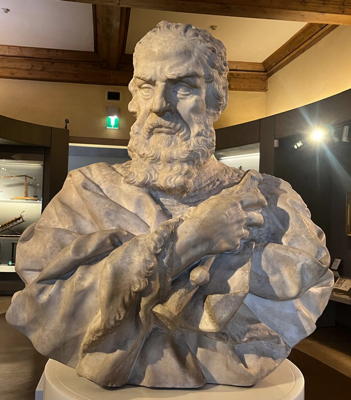

Here is my picture of Galileo in Room VII of the Museum.

There are displays relating to Viviani, for example

There is a text stating:

Galileo's last pupil, Vincenzo Viviani (1622-1703), collected and made mathematical instruments. He left his collection to the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, which in turn donated it to the Florentine Imperial and Royal Museum of Physics and Natural History. From here the collection went on to the University of Florence, and lastly to the Museo Galileo. It includes a variety of artefacts that reveal Viviani's particular interest in astronomy: the measurement of time and the structure of the universe.

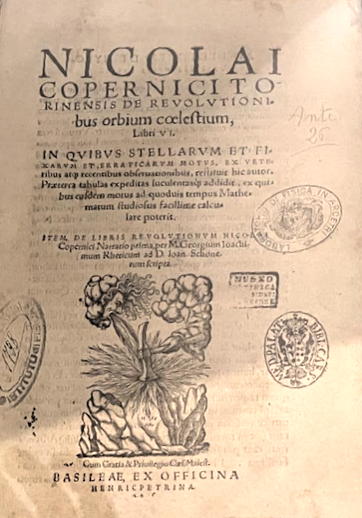

The Galileo Museum contains many other items of interest. For example, related to scientists with a biography in MacTutor, the is a copy of Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium coelestium and a book showing Brunelleschi's construction of the cupola of the Duomo

Before leaving the Galileo Museum we went to the Interactive Room. In that room there are working models to allow one to carry out experiments similar to those that Galileo performed concerning the laws of motion. For example there is a model to illustrate the brachistochrone descent which Galileo studied in 1602. Galileo showed that a body descending along a straight line to reach a point on an adjacent vertical line would arrive most rapidly by travelling at 45º to the vertical. He then showed that a body travelling along the arc of a circle would reach the point on the vertical line sooner that one travelling along a straight line. The model in the Interactive Room lets one release two balls at the same time, one rolling down a straight line and the other down the arc of a circle and show that Galileo was right. He did believe, however, that the arc of a circle would be the quickest path which Johann Bernoulli showed to be incorrect: Johann Bernoulli showed that a cycloid is the most rapid path in 1697.

There is also an entertaining model illustrating Galileo's discovery of parabolic motion. There is a gun firing projectiles and you can choose the target to aim at and the angle that the gun will fire. I wasn't very successful in hitting the target! Another model illustrates Galileo's discovery that the distances travelled by a ball rolling down an inclined plane are proportional to the square of the time it takes to fall.

Take the Lungarno Generale Diaz alongside the River Arno and pass a statue of Galileo just as you reach the Uffizi Gallery.

7. Uffizi Gallery.

Piazza della Signoria.

Contains a portrait of Galileo and a Mathematics Room.

Before entering the Uffizi Gallery you can see a statue of Galileo in the loggia.

The Uffizi Gallery is a wonderful art museum containing an amazing collection of priceless paintings, particularly from the Renaissance period. Construction began in 1560 as a building to house the administration with Giorgio Vasari as the architect appointed by Cosimo I de' Medici. The building was complete in 1581 and slowly more and more rooms were used to exhibit paintings.

The painting in the Uffizi Gallery which is relevant to our Galileo tour is a portrait of Galileo by the painter Justus Suttermans (1597-1681) which he painted around 1635. Here is my photograph of the painting.

The following information is displayed beside the painting:

Galileo is shown here at the age of 71, after he was convicted of heresy by the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman Inquisition and sentenced to house arrest. He served out his sentence in the Villa Il Gioiello at Pian dei Giullari, in the countryside around Arcetri, where he died in 1642. Wearing a black doctoral gown with a white ruff, he is immersed in an atmosphere of luminous authority. In this room, on the opposite wall, there hangs a portrait of Grand Duke Cosimo II, whom Galileo tutored in mathematics as a young boy and to whom he later dedicated his Sidereus Nuncius, in which he announces the discovery of Jupiter's moons (the "Medici Planets").

The Uffizi Gallery had other connections to mathematical instruments, and in particular to some belonging to Galileo. The collection was started by Cosimo I de' Medici and housed at first in the Map Room of the Palazzo Vecchio. During Ferdinando I's rule, from 1587 to 1609, the collection was moved to two rooms in the Uffizi Gallery. Here is the text displayed in the Galileo Museum:

The Science of Warfare: In 1599 Ferdinando I (1549-1609) had the mathematical instruments moved from Palazzo Vecchio to a room dedicated to military architecture in the Uffizi Gallery. The new display explicitly celebrated the "science of warfare" which, with the spread of firearms, had transformed battlefields into a theatre of geometric studies. Mortars compelled modifying the geometry of fortresses. Moreover, a suitable knowledge of the ratio between the weight and range of cannonballs was now required, calling for precise measurement and computation operations. Men of arms were obliged to acquire basic mathematical principles for the perfect management of military operations. As stated by Galileo (1564-1642) for the noblemen who attended his lessons in mathematics, a soldier should have a basic knowledge of arithmetic, geometry, surveying, perspective, mechanics and military architecture. This new approach to war favoured a vogue for collecting scientific instruments at court that swept through Europe as an intellectual celebration of the art of war.

Ferdinando I had two rooms in which to display the mathematical instruments, one entitled Cosmography and the other Military Architecture. In addition to the instruments, the rooms contained navigation charts, maps, models of machines and of fortresses. The Military Architecture Room was decorated with frescos and today the room is called the Little Room of Mathematics. The frescos were painted between 1599 and 1600 by Giulio Parigi and Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Euclid and especially Archimedes are represented and celebrated in these frescos. Here are two pictures I took of the frescos.

In the second of these you see the central panel of the ceiling which represents Mathematics.

Here is another picture of the Mathematics Room.

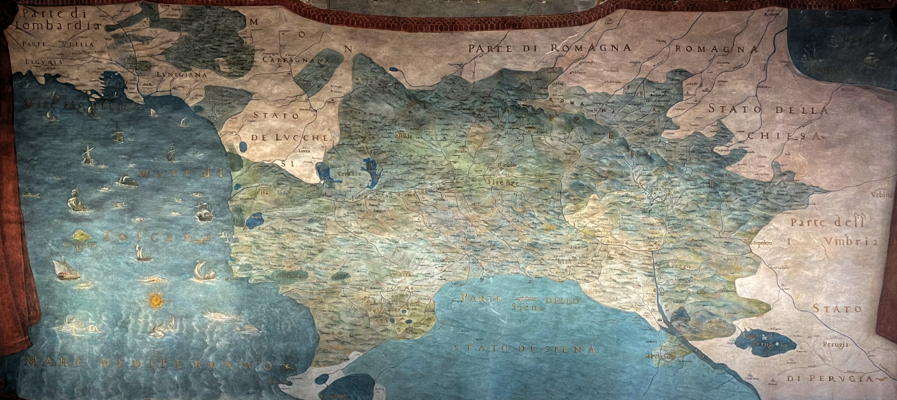

Adjacent to the Mathematics Room is the Terrace of the Map Room of the Uffizi which was the Cosmography Room. In this room, following Galileo's death, two of his instruments were displayed in the room, the geometric and military compasses and his telescope. These were appropriate to the Map Room since it was hoped that Jupiter's satellites, christened the Medicea Sidera by Galileo, would solve the longitude problem and give political and military power to the Medici. Francesco I commissioned maps of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany for the room which were painted by Ludovico Buti. Here is the map of Tuscany and the view from the room.

In 1775 the contents of these two rooms were moved to the Imperial-Royal Museum for Physics and Natural History Museum near the Pitti Palace which had been founded in 1771. Today the museum is known as Museo Storia Naturale - La Specola.

From the Lungarno degli Archibusieri take the Lungarno degli Acciaiuoli.

8. Church of Santa Trinita.

Piazza di Santa Trinita.

Viviani claimed that Galileo "learned the precepts of logic from a Vallombrosan teacher of S Trinita."

The Church of Santa Trinita was founded by the Vallombrosians in the 11th century but the church that we see today was constructed on the site of the earlier church between 1258 and 1280. We know that Galileo attended schools in Pisa between 1569 and 1574. His father had moved to Florence when Galileo was a young child and in 1574 Galileo joined his father in Florence. There he studied the humanities, Greek and dialectics before continuing his studies with the Vallombrosian monks. The Vallombrosian are a religious order named after the location where they were founded in the 11th century in Vallombrosa about 30 km from Florence. It was a Benedictine styled order but insisted on an extremely austere way of life. We know that Galileo became a novice of the order but it is not known whether he studied with the Vallombrosan monks in the monastery of Vallombrosa or in the community of Santa Trinita. The only reference to him studying at Santa Trinita is the one by Viviani quoted above. It is certain, however, that he studied Aristotelian logic with the Vallombrosians for several notes in his own hand relating to these studies are still extant. His father didn't allow him to complete his studies with the Vallombrosians, which greatly annoyed the Abbot, and Galileo returned to Pisa where he entered the university.

Cross the River Arno on the Ponte Santa Trinita to the Piazza de' Frescobaldi. The Via Santo Spirito followed by the Via dei Serragli and Borgo Stella goes to the Piazza del Carmine.

9. Church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

Piazza del Carmine.

Burial site of Galileo's mother.

The Church of Santa Maria del Carmine was started in 1268 but was not completed until 1476. From the time of Galileo's sojourn in Padua, the family home was located within the parish of Santa Maria del Carmine. Galileo's mother Giulia Ammannati (1538-1620) lived there and his sister, Virginia Galilei, probably resided there with her husband Benedetto Landucci. Galileo's mother was buried in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in 1620.

The church that you see today is different from the one that was there in Galileo's time since the original building was largely destroyed by fire in 1771 and reconstructed in its present form in 1775. You can still see the 14th century frescos in the sacristy, the Corsini chapel (designed in the Baroque period by Pier Francesco Silvani) and the Brancacci chapel.

Take the Via del Leone to the Via Villani.

10. Villa dell'Ombrellino.

Via Roti Michelozzi.

Galileo's residence between 1617 an 1631.

This villa was certainly built by the 14th century when it was known as the Villa di Bellosguardo, being named after the hill where it was located. From the time Galileo was a professor of mathematics at the University of Padua, beginning in 1592, Galileo's mother Giulia Ammannati and sister Virginia were living at the Villa di Bellosguardo. Between 1616 and 1617 at Bellosguardo, Galileo performed a series of astronomical observations on the mean motions of the moons of Jupiter (which he called the Medicea Sidera) and constructed the relative Tables. Together with Benedetto Castelli, he also observed the stars in the tail of the constellation of Ursa Major.

From 1617 to 1631 Galileo lived at Bellosguardo and there wrote Il Saggiatore (The Assayer) and the Dialogo sui massimi sistemi (Dialogue Concerning the Chief World Systems), before moving to Arcetri. Galileo did not like living in the city, and always lived between Bellosguardo and Arcetri.

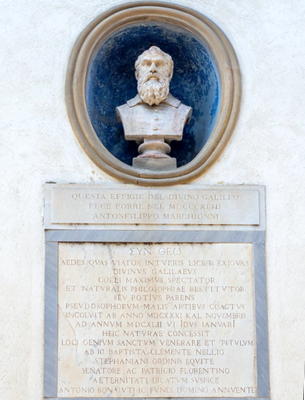

In 1815 the Villa was renovated by the countess Teresa Spinelli Albizi and its name changed to Villa dell'Ombrellino. Here is a picture of the Villa dell'Ombrellino today, and also a picture of the bust of Galileo Galilei with commemorative plaque inside the entrance loggia of the Villa.

From the Via del Leone take the Viale Francesco Petrarca to the Via del Campuccio. Just where it joins the Via Romana is the Museo Storia Naturale - La Specola.

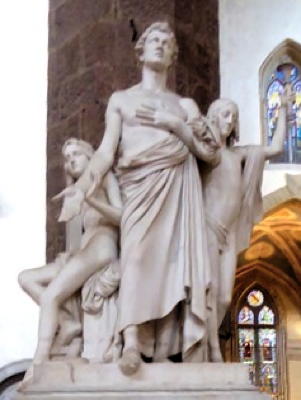

11. Tribune of Galileo.

La Specola Museum, Piazza de Pitti.

The tribune, built to commemorate Galileo, was completed in the Science Museum of La Specola in 1841.

The Galileo Museum gives the following information:

Built at the initiative of Grand Duke Leopoldo II of Lorraine and situated in Palazzo Torrigiani, the Tribune of Galileo was inaugurated in 1841 on the occasion of the Third Congress of Italian Scientists. The building, designed by the Florentine architect Giuseppe Martelli, was erected in honour of Galileo Galilei and was conceived as an iconographic synthesis of experimental science. It is a monument unique of its kind, a "Scientific sanctuary", as it was called by Vincenzo Antinori, at the time director of the Museum of Physics and Natural History. The work presents a rich iconographic display, with frescoes and bas-reliefs depicting instruments, scientific discoveries and the scientists who made them possible.

Here is a picture of the Tribune.

At the centre of the Tribune's hemicycle stands the statue of Galileo sculpted by Aristodemo Costoli.

In particular, the seven lunettes display, with the rhetorical commemoration typical of the 19th century, the development of experimental science according to a precise, linear chronological sequence. Galileo, of course, is at the centre of the iconographic narration. In the second lunette, Galileo is shown demonstrating the law of falling bodies; in the third we see him intent on observing the lamp in the Cathedral of Pisa; in the fourth, as he presents his telescope to the Venetian Senate; in the fifth Galileo, by now elderly and blind, converses with his disciples.

The mathematical instruments which had been displayed in the Uffizi gallery and then the Museum of Physics in the Palazzo Torrigiani were displayed in the Tribune of Galileo from 1841.

Take the Via Romana to the Piazza de' Pitti, then the Via de' Guicciardini to the Piazza Santa Felicita. Then the Piazza dei Rossi which becomes the Costa San Giorgio.

12. Galileo's house.

Costa San Giorgio.

Galileo lived in this house between 1629 and 1634.

The Costa San Giorgio is the location of the houses that the Galilei family purchased in the period between 1629 and 1634. The first house was sold by Iacopo Bramanti Boschi to Vincenzo Galilei, Galileo's son, on 20 December 1621. The second house was sold by Iacopo Zuccagni to Galileo on 18 August 1634. There was a dispute with Zuccagni about this house, because he did not acknowledge that Galileo had bought it until the Supreme Magistrate acknowledged that it was owned by Galileo. Today, on the facade, we can see the coat of arms of the Galileo family and his portrait.

From the Costa San Giorgio take the Via di S Leonardo for 1.2 km to the Via Vincenzo Viviani followed by the Via del Pian dei Giullari.

13. Villa Il Gioiello.

Museum System of the University of Florence.

Via del Pian dei Giullari.

Home of Galileo in his final years after he was condemned to house arrest by the Holy Office in 1633.

The Villa Il Gioiello is also known as the Villa Galileo although this is somewhat ambiguous since, as we have seen, Galileo lived in various houses in Florence.

We give a slightly modified version of the text by the Galileo Museum:

The villa, the origin of which seems to date to the 14th century, was rebuilt in the 16th century. The name "Gioiello" (Jewel) indicated the favourable location of the property, situated westwards in the hills of Arcetri. In remembrance of Galileo Galilei who lived here during the last years of his life, the facade conserves a bust from 1843 and two plaques (1788 and 1942).

It was Galileo's daughter, Virginia, who informed her father in August 1631 of the possibility to rent the villa adjoining the monastery of San Matteo in Arcetri (both of Galileo's daughters had become nuns in this monastery: Virginia in October 1616 with the name of Suor Maria Celeste, and Livia in October 1617 with that of Suor Arcangela). Galileo stipulated the lease contract in September 1631. As his biographer Niccolò Gherardini narrates, Galileo "would spend many continuous hours in his garden, tending with his own hands all the pergolas and rows of grapevines, with such symmetry and proportion that it was a worthy thing to see."

After being condemned by the Tribunal of the Holy Office on 22 June 1633, Galileo was the guest of Archbishop Ascanio Piccolomini in Siena, as it was unwise to proceed to Florence, stricken by the plague. On 1 December 1633, the Congregation of the Holy Office permitted the scientist to return to "Gioiello", but he was forbidden to receive guests with whom he could discuss scientific topics. In the last days of the year, he received the visit of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinando II de' Medici. Only in January 1639, given his precarious health conditions, was he permitted to host the young Vincenzo Viviani who, three months before the death of the famous scientist, was joined by Evangelista Torricelli.

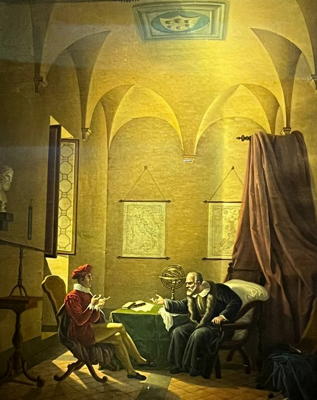

Galileo also met the poet John Milton in the Villa Il Gioiello in the summer of 1633. Annibale Gatti (1828-1909) painted the meeting in the second half of the 19th century and the oil painting now hangs in the Galileo Museum. Here is my photograph of the painting.

Galileo ended his days in the Villa Il Gioiello assisted by his son Vincenzo, Torricelli and Viviani. In his Racconto Istorico della Vita del Sig.r Galileo Galilei, Viviani describes the maestro's final moments: "With the unforeseen development of a very slow fever and palpitations of the heart, after two months of an illness that little by little consumed his spirits, on Wednesday, 8 January 1641 ab Incarnatione [8 January 1642 by today's calendar], at four in the morning, and at the age of seventy-seven years, ten months and twenty days, with philosophical and Christian constancy, he gave up the soul to the Creator, sending it, as much as faith agrees, to enjoy and more closely admire the eternal and immutable wonders that fragile artifice, great thirst and impatience had permitted the eyes of we mortals to approach."

Take the Via del Pian dei Giullari to the Via San Matteo, Arcetri.

14. Convent of San Matteo .

Via San Matteo, Arcetri.

Poor Clares convent where Galileo's daughters Livia and Virginia (Sister Maria Celeste) lived.

The Poor Clares had been founded by Clare of Assisi (1194-1253) who was a friend and student of St Francis of Assisi. The nuns of the order had no possessions and the order was built around poverty. Galileo's daughters were both nuns in the Convent of San Matteo in Arcetri, outside Florence, which had been founded in 1309. Both girls were placed in the convent in 1613 after Galileo obtained a dispensation from Cardinal Maffeo Barberini. A dispensation was required since the girls were too young to make the decision themselves. Virginia (1600-1634) took the veil in October 1616 and the name Sister Maria Celeste, while Livia (1601-1659) took the veil in October 1617 taking the name Arcangela. At this time daughters would have been required to marry or enter a convent. Galileo would have been required to put up a dowry if his daughters had married and most convents would also require a substantial dowry to accept a girl. The Poor Clares, however, did not require a dowry although the sisters would request money from their relatives. In fact Maria Celeste frequently wrote to her father asking for money. Although one would imagine that a man in Galileo's position would have been able to afford sizeable dowries for his daughters, this may not have been the case and having his daughters enter a Poor Clares convent may have been a financial necessity for him. On the other hand, both Virginia and Livia were registered as having been born outside marriage and Galileo may have felt that this gave them little hope of marriage.

The Galileo Project writes about Virginia (Maria Celeste):

The convent of San Matteo was very poor. The nuns did not have the wherewithal to feed themselves and keep the buildings in repair. Maria Celeste wrote to her father that the bread was bad, the wine sour and that they ate ox meat. Galileo helped repair windows and personally took charge of keeping the convent clock in good repair. Maria Celeste often had to appeal to her father for help, and she was chronically ill. She bore her ill health with dignity and courage, and managed to be a great comfort to her father. She worked constantly to mitigate the difficulties between Galileo and her brother Vincenzio.The Science Museum writes about Livia (Arcangela):

In contrast to Virginia, Livia did not adjust well to convent life. Her frequent illnesses and indispositions were probably due to her rejection of the harsh convent life. Also, her lack of responsibility toward the tasks she was assigned often led Virginia, though without guile and with great concern, to report on her to their father. Although there is no evidence of resentment toward Galileo, the harsh life at San Matteo probably created ill feeling between father and daughter, which time did nothing to alleviate.

Written by J J O'Connor and E F Robertson

Last Update December 2025

Last Update December 2025