Choi Seok-jeong

Quick Info

Chopyeong-myeon, Jincheon-gun, South Korea

Chopyeong-myeon, Jincheon-gun, South Korea

Biography

Choi Seok-jeong's father was Choi Choi-ryang, and his mother was An Hunjing. It was a family of scholars, diplomats and politicians in the Joseon Dynasty of Korea. The Joseon Dynasty ruled Korea for five hundred years from around 1400 to 1900. Choi Seok-jeong's grandfather Choi Myeong-gil (1586-1647) was a neo-Confucian scholar who held several important posts in the government. This was a very difficult time in Korea since the Chinese Qing invasion of Joseon in the winter of 1636 led to the Joseon becoming completely defeated and left the Chinese Qing Dynasty in control. At this time Choi Myeong-gil was Jwauijeong, the Second State Councillor of the Uijeongbu (State Council), and he went to Shenyang in China in 1637 to negotiate the release and repatriation of Korean prisoners of war. In 1643 he was imprisoned in Shenyang and detained for two years. After his death, he was severely criticised by neo-Confucian rationalists for insisting on reconciliation and compromise. He died when Choi Seok-jeong, the subject of this biography, was one year old. The consequences of the war with the Qing were, however, far reaching and when Choi Seok-jeong became a leading politician he had to concentrate on the Joseon's recovery.Choi Seok-jeong had a younger brother Choi Seok-hang (1654-1724) who also became an important politician. He was described as follows:-

Although he was small and shabby in appearance, he was accurate in his judgment and received a reputation as one of the best among the politicians.By the age of 9, Choi Seok-jeong had already memorised the Book of Songs, a Chinese Confucian classic collection of poems, and The Book of Records, a history chronicle. By the age of 12, he had reached the level of being able to understand the Zhou Yi, the ancient Chinese divination text whose name is often translated as 'Book of Changes' or 'Classic of Changes'. This was a remarkable achievement and he was widely considered as a child prodigy. He also studied the writings of Park Se-chae (1631-1695), the author of many texts.

At the age of 17, he began his career as a civil servant and, in 1671 he took the examination which saw the start of his political career [3]:-

As a professional bureaucrat, he did not cling to his cause but he took care of the people's difficulties, tried to reform political evils, and tried to reduce the anger caused by conflict in his political party.Together with Yun Jeung and Nam Gu-man, Choi Seok-jeon led the political party known as the Soron. It was a period of great political instability with disagreements leading to political parties splitting up and new parties forming. The Soron, meaning 'young learning', had formed when the Westerners political party split in 1683. Choi Seok-jeo served in many capacities, for example in 1699 when Sukjong was King, he was Jwauijeong, the Second State Councillor of the Uijeongbu (State Council). He served as Yeonguijeong, the Chief State Councillor of the Uijeongbu (State Council), in 1701, 1702-03 and 1705-10. This role would best be described as equivalent to that of a modern prime minister. As a leading political figure, he had his portrait painted. It is the one displayed beside this biography [10]:-

In this portrait, Choi Seok-jeong is depicted wearing a green, round-collared official robe and a black satin hat, sitting in a chair covered with leopard fur, with his hands held together inside the sleeves of his robe. His feet, encased in black leather shoes, rest upon a footstool which is, in turn, placed upon a woven rush mat with a floral design. The chest of his robe bears a large square rank badge embroidered with twin cranes, while the exclusive rhinoceros horn belt worn around his waist symbolises his status as an official of the Major First Rank. The artist used outlining and shading techniques originating from Western art to create a more three-dimensional effect in his depiction of the sitter's face. The painting is regarded as a rare and important example of the official portraits of the early eighteenth century, which tended to be more natural in terms of their execution when compared with portraits of meritorious subjects from the seventeenth century, whose subjects tended to be expressed with greater volume and rigidness of posture.He made many visits to China and learned of the advances in science and technology through Western contacts. This led to him being keen to promote the use of books such as the Tongwen Suanzhi in Korea. This book was a Chinese text based on the writings of Christopher Clavius and Michael Stifel as transmitted to China by Matteo Ricci.

There is much more that could be said of the political career of such an important politician at a fascinating period in Korean history, but since this site is concerned with the history of mathematics, we must turn to Choi Seok-jeong's mathematical contributions. We learn a little of his mathematical work through letters he wrote to Lee Segu (1646-1700) [9]:-

Choi Seok-jeong and Lee Segu studied Western calendars and mathematics together around 1683, and in addition to direct exchanges, they continued to exchange letters and discuss academic issues. There are 24 letters written by Choi Seok-jeong to Lee Segu on arithmetic, astronomy, and calendars which reflect their research together.Before looking at some of Choi Seok-jeong's major mathematical contributions, let us explain what Latin squares are, what orthogonal Latin squares are, and how magic squares are made from pairs of orthogonal Latin squares.

A Latin square is an arrangement of symbols in cells arranged in rows and columns such that each symbol occurs once in each row and in each column. Such a Latin square is said to be of order . If two Latin squares of the same order are superimposed on one another and if each pair of symbols in the resultant array occurs only once they are called orthogonal Latin squares. A square array of the integers is called a magic square if the sums of the numbers in each row, each column, and both main diagonals are the same. This sum will be . To obtain a magic square from two orthogonal Latin squares, replace each pair in the superimposed orthogonal Latin squares by .

Magic squares have been known since 650 BC, and in all probability, from much earlier than that. Although Latin squares were certainly known in the 12th century, for long time it was thought that the idea of orthogonal Latin squares was first introduced by Euler in 1782. This, however, is not the case since an example of two orthogonal Latin squares of order 9 appear in the book "Gusuryak" written by Choi Seok-jeong. Sangwook Ree explains in [13] that Choi Seok-jeong:-

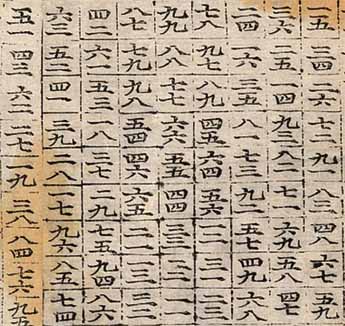

... wrote a mathematical book titled "Gusuryak" in 1715-1718. Joseon had begun to be introduced to Western culture in about that time. He had certainly read the book "Cheonhakchoham," which introduced Koreans to the Western world, but his academic knowledge was based on Confucianism. In his book "Gusuryak," he was trying to understand mathematics on the basis of the ancient Asian philosophy of I Ching. In that philosophy, all things in the universe originate from yin and yang in dynamic balance, a theory called taegeuk, from which four symbols, the sasang, emerge. This idea conveys a sense of change in the universe. The taegeuk and the sasang are both elements of the national flag of Korea. Asian traditional mathematics was based on the "Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art." Choi classified mathematical operations, problems and all nine chapters into four classes, represented by the four sasang symbols. Trying to understand mathematics and patterns with those four symbols, he produced a remarkable study of magic squares and related topics, in particular an orthogonal Latin square of order 9. This is an accomplishment predating Euler's work by more than 60 years.Here is a picture of the orthogonal Latin squares of order 9 as they appear in the "Gusuryak":

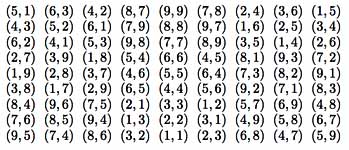

Here is Choi Seok-jeong's orthogonal Latin squares of order 9 in modern notation:

From the orthogonal Latin squares, he was able to construct a magic square of order 9.

Let us note that Choi Seok-jeong comments in "Gusuryak" that he was unable to construct orthogonal Latin squares of order 10. In fact Euler also failed in an attempt to construct orthogonal Latin squares of order 10 and conjectured in 1782 that orthogonal Latin squares of order did not exist for integers of the form . It was not only Choi Seok-jeong and Euler who failed to construct orthogonal Latin squares of order 10 for attempts to construct such a square became an obsession for many mathematicians over the years. In 1959 Ernest Tilden Parker (1926-1991) found two orthogonal Latin squares of order 10 using a computer search. It was one of the earliest combinatorial problems solved using an electronic computer.

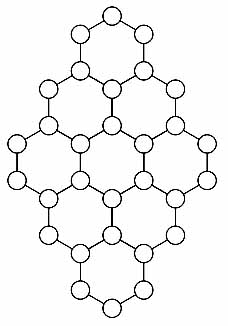

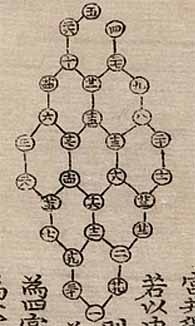

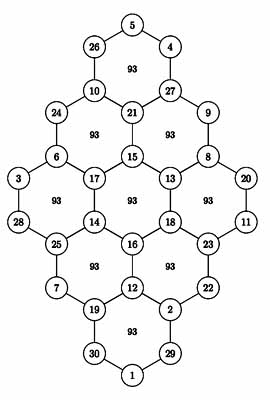

There is another fascinating problem invented by Choi Seok-jeong which appears in the "Gusuryak", namely the Hexagonal Tortoise Problem. Let us illustrate the problem with the example from "Gusuryak". Here is a lattice with 9 hexagons:

The problem is to assign the numbers 1, ..., 30 to the 30 vertices of the hexagons so that the sum of the vertices of each hexagon is the same. Here is Choi Seok-jeong's solution from the "Gusuryak":

Here is Choi Seok-jeong's solution in modern notation:

The problem clearly generalises and is of considerable interest today because of its application to coding theory.

Although we have recorded some brilliant highlights from the "Gusuryak", it was on the whole not quite such a stunning work as this suggests [13]:-

From a mathematical perspective, "Gusuryak" is not as good as perhaps 24 other books by mathematicians of the Joseon period. But his idea of trying to understand mathematics according to the principle of the change of the universe given in I Ching is considered unique, and the orthogonal Latin square is a major accomplishment.In [9] Lee Sang-Gu and Lee Jae Hwa ask "how was it possible to write an academic book while busy with politics?" They have found some evidence that Choi Seok-jeong was able to write the work when taking a break from politics due to illness.

Joseson suffered a series of invasions from Japan beginning in 1592 and from the Quin Dynasty of China in 1636-1637, and lost all its national records and books. "Gusuryak" was a big help for Joseson to recover its mathematics and related science and technology. Choi's study of magic squares contained some results never seen in Chinese mathematics, and other results are applicable today to the hexagonal tortoise problem of coding theory.

After resigning from his government positions, Choi Seok-jeong lived mainly at the foot of Sorae Mountain. Soraesan is a mountain in the region bordering Siheung and Incheon. It is located near the present-day Incheon Grand Park. While he was there he wrote a poem which, of course, is impossible to translate into English. The following, however, gives the gist of some ideas in it:-

The foot of Soraesan Mountain is a good place to live, so even if you are not old, you are relaxed.It is only in recent years that Choi Seok-jeong's contributions to mathematics have been fully recognised. In the second edition of the Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2007) edited by Charles J Colbourn and Jeffrey H Dinitz, there is the following on page 12:-

There are many loud noises the wild crane over the wind.

After the snow falls, a couple of plum blossoms on the river bank are blooming, but how can I build a fortress wall with my academic skills rather than doubt?

I read Yang Woong's writing and found out the village trail is not too small, the real music is only in the fire.

The literature on latin squares goes back at least 300 years to the monograph 'Koo-Soo-Ryak' by Choi Seok-Jeong (1646-1715); he uses orthogonal latin squares of order 9 to construct a magic square and notes that he cannot find orthogonal latin squares of order 10.Choi Seok-jeong was appointed to the Korea Science & Technology Hall of Fame on 23 November 2013 by the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Korean Academy of Science and Technology. On 6 September 2018, a ceremony was held to commemorate the completion of the Choi Seok-jeong seminar room at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. On 16 April 2019, South Korea issued a 330 South Korean won stamp in his honour. See THIS LINK.

References (show)

- M A Amela, A Sextuply Self-Orthogonal Latin Square of Order Nine and their Magic Squares.

https://budshaw.ca/documents/6-SOLS%209x9.pdf - Choi Seok-jeong (Korean), Korean Wikipedia.

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/최석정

- Editorial Board, Opened a lecture hall to commemorate the Joseon Dynasty mathematician Choi Seok-jeong (Korean), Department of Mathematical Sciences, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (25 November 2018).

https://mathsci.kaist.ac.kr/newsletter/article/최석정-기념-강의실-개설/ - Editorial Board, Opening of Choi Seok-jeong Seminar Room, Department of Mathematical Sciences, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (September 2018).

https://mathsci.kaist.ac.kr/home/en/2018/09/opening-of-choi-seok-jeong-seminar-room/ - Jon-Lark Kim, Dong Eun Ohk, Doo Young Park and Jae Woo Park, Recent results on Choi's orthogonal Latin squares, arxiv.org (2021).

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1812.02202.pdf - Kim Cheong-han, Choi Seok-jeong, a mathematician, a fusion talent in Joseon (Korean), KISTI's Scientific Scent No. 2460 (24 August 2015).

http://scent.kisti.re.kr/site/main/archive/article/history-조선의-융합인재-수학자-최석정 - Kim Hyun-min, Choi Seok-jeong, Joseon's greatest mathematician (Korean), Atlas News (23 August 2020).

http://www.atlasnews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=2568 - Ko-Wei Lih, A remarkable Euler square before Euler, Mathematics Magazine 83 (2010), 163-167.

- Lee Sang-Gu and Lee Jae Hwa, Mathematical work of Choi Seok-Jeong and Lee Se-Gu (Korean), Journal for History of Mathematics 28 (2) (2015), 73-83.

- Portrait of Choe Seok-jeong and Case, Cultural Heritage Administration, Daejeon Government (2000).

- Ryu Kyung-dong, Joseon Dynasty mathematician Choi Seok-jeong, inducted into the Science and Technology Hall of Fame (Korean), Electronic Times News (7 October 2013).

https://m.etnews.com/201310070407 - Sang-Geun Han, Seok-Jeong Choi and his Koo Su-Rak (Korean), Newsletter of the Korean Society for Mathematical Education 14 (2) (1998).

- Sangwook Ree, Choi Seokjeong and traditional Asian mathematics: Confucian scholar's discovery predates the work of Euler, Math&Presso, International Congress of Mathematicians Seoul 2014 No 3 (15 August 2014).

- Seokki Kang, Seok-Jeong Choi who beat Euler (Korean), Channel Coding Lab, Yonsei University.

http://coding.yonsei.ac.kr/article-2008-08.htm - Seongsuk Kim, Orthogonal Latin Squares of Choi Seok-jeong, Poster, History od Pedagogy of Mathematics, 16 July - 20 July, DCC, Daejeon, Korea.

- Seongsuk Kim and Mikyung Kang, Choi Seok-jeong's Orthogonal Latin Square (Korean), Journal of the Korean Society of Mathematical History 23 (3) (2010), 21-31.

- Yoon-Yong Oh and Sang-Geun Han, Seok-Jeong Choi and his Ma Bang-Jin (Korean), Journal of the Korean Society for Mathematical Education Series A 32 (3) (1993), 205-219.

Additional Resources (show)

Other pages about Choi Seok-jeong:

Other websites about Choi Seok-jeong:

Cross-references (show)

Written by J J O'Connor and E F Robertson

Last Update March 2022

Last Update March 2022